Darwin's Finches

The Galapagos Islands, where Charles Darwin first spotted his infamous finches (picture: NASA, public domain)

Here’s how the story goes.

Two days after Christmas in the year 1831, at the tender age of 22, Charles Darwin hops on a boat named the Beagle and sets off from Plymouth harbour on an epic round-the-world voyage.

One of the stops is the Galápagos - a cluster of small islands around a thousand kilometers off the coast of Ecuador - where the young naturalist observes and collects a number of different finch specimens.

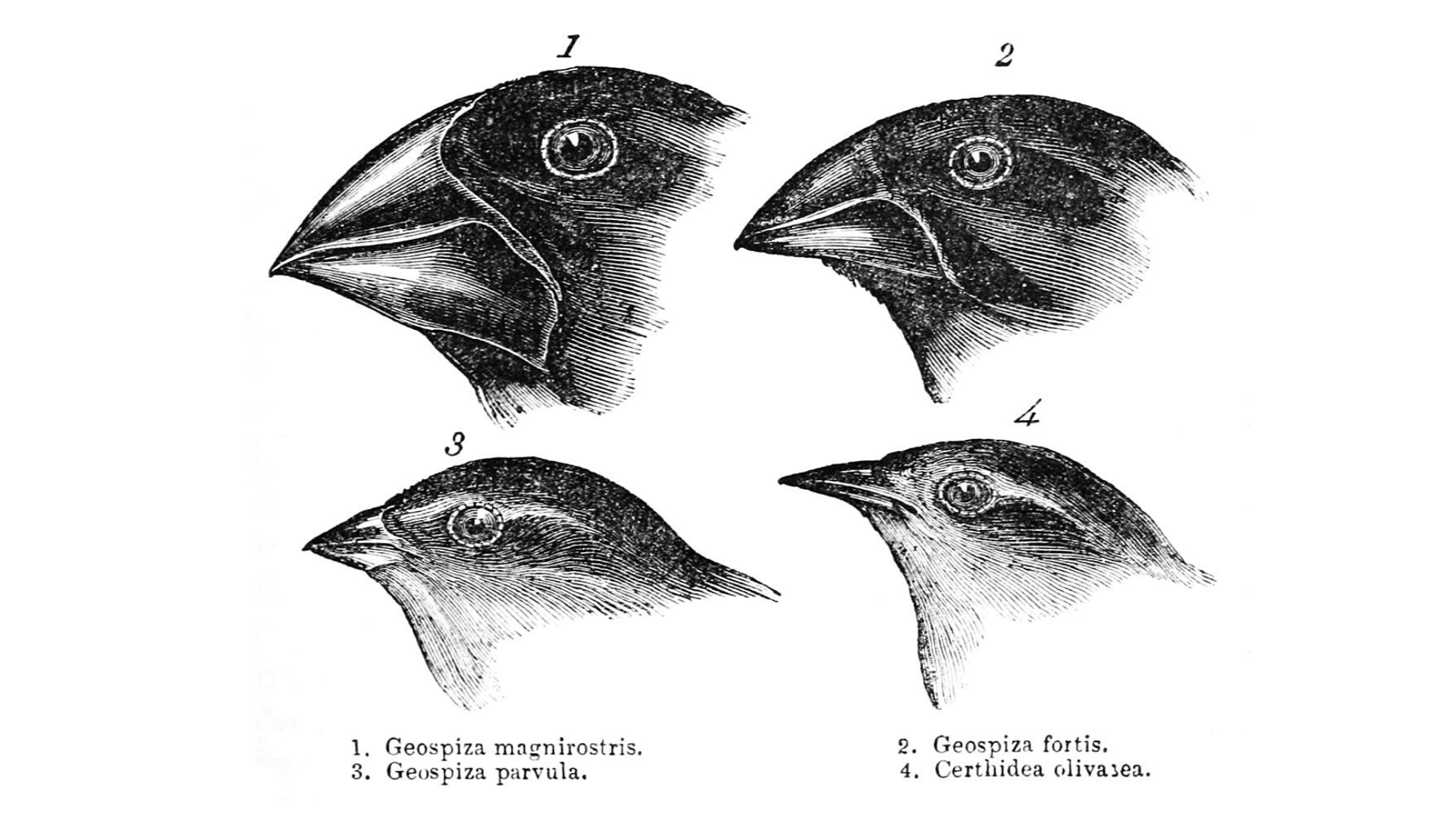

Comparing the finches from each island, he notices that they’re all broadly similar but with some varying features, such as the size and form of their beaks, and the shape of the claws. Each one seems perfectly suited to the different foodstuffs available on each island - seeds on one, nuts on another, berries on another and so on.

Suddenly it was crystal clear! The birds must have all descended from a common ancestor and then been isolated on each island, evolving separately to exploit the resources available.

These diverse species became the inspiration for perhaps the greatest scientific idea of all time - the theory of evolution by natural selection, as detailed in his book, Origin of Species, which was finally published decades later.

As a result, the birds became known as ‘Darwin’s finches’, earning themselves a place in history as a true icon of evolution. Well, hold up just a second… because while it’s a nice tale, it’s not actually true.

It turns out that although Darwin did collect finches while he was in the Galápagos, he didn’t pay much attention to them at all at the time.

Initially, he believed that they were such a diverse set of birds that they couldn’t be closely related. He was more interested in the links between species on the islands and on nearby continents, focusing instead on mockingbirds.

When Darwin returned to England in 1837, he gave his finch collection to John Gould, a famous ornithologist. It was Gould who pointed out to Darwin that the birds were more similar than Darwin had first thought, belonging to 12 closely related but distinct species.

With this revelation, Darwin realised that if the individual finch families were confined to different environments, this might account for the evolution of their different physical characteristics.

Unfortunately, Darwin had been so uninterested in the finches at the time that he hadn’t recorded exactly where he had collected his specimens.

He ended up having to consult others who had been in the Galápagos with him and who had collected and properly labelled their own specimens to try to piece together where all the different species of finch were found.

Darwin's Finches, from "Voyage of the Beagle" by John Gould (public domain)

Eventually, Darwin was able to piece together enough evidence to support his wider theory that one species could transform into another over time. He published his comparison of finches in 1845, accompanied by the now iconic illustration highlighting the different beaks of the birds.

He wrote:

‘Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.’

But although Darwin did eventually find the finches at least a little bit interesting, they were just bit players in Darwin’s theory of evolution.

While he does discuss the divergence of birds in the Galápagos in his most famous book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, published over a decade later in 1859, he doesn’t specifically address the finches at all.

So while the finches of the Galápagos can’t take credit for inspiring Darwin’s theory of evolution, they did help develop it and provided evidence to support it. But how have they become so inextricably linked to the great man and his ideas?

The first person to use the phrase “Darwin’s Finches” was English surgeon and ornithologist Percy Lowe, who first coined it in 1936 - more than 50 years after Darwin’s death. But the person who really popularised the concept of Darwin’s finches was David Lack in his book of the same name, published in 1947.

I do wonder if this is an author attempting to get a bit of publicity by trading on someone else’s fame, as Lack actually based his book on a bunch of finches collected by an American expedition to the Galápagos at the turn of the 20th century, rather than Darwin’s own collection of birds. Either way, the name has stuck - and so has their scientific interest.

Peter and Rosemary Grant, a husband and wife pair of evolutionary biologists at Princeton University, spent 40 years studying the finches on an isolated and uninhabited island in the Galápagos called Daphne Major.

While it might sound bleak this is the perfect place to study evolution in action, as the island is home to 13 species of finch, including 6 species of ground finch.

It was the medium ground finches, which eat seeds on the ground, that the Grants chose to study, capturing, tagging and tracking around 20,000 birds during their four decades of research. They carefully weighed and measured the birds, took blood samples and recorded their songs.

The first few years of the study were relatively uneventful. Then in 1977, drought hit the island. The dry conditions meant that there were fewer seeds available, and those that remained were larger and harder on average than in the previous seasons.

As the Grant’s described it, ‘beaks are tools’, and these finches needed the right tool for the job. Alas, the drought killed off 85% of the island’s medium ground finches. And the birds who survived were those with relatively large beaks that could crack large seeds.

Their offspring also had larger beaks, leading to a lasting increase in the average beak size of the species. The Grants had caught evolution in action. So Darwin was right: changes in food supply do drive changes in physical characteristics.

While they may not be the evolutionary inspiration that they’re sometimes made out as, Darwin’s finches are still considered textbook examples of how a single species can differentiate into several new ones to exploit the available resources.

And thanks to genetic sequencing, we now know that all 13 species of Galápagos finch are more closely related to each other than mainland finches, confirming Darwin’s suspicion that they did indeed have one common ancestor.

In fact, the birds are so closely related that there has been some debate about whether they are separate species at all. According to the Grants, they think they’re somewhere in evolutionary limbo, not quite separate species, but somewhere in the ‘grey zone’ in between.

Unfortunately, as is the case for so many of the species on our planet, the birds of the Galápagos are now battling extinction.

Around 80% of the birds of the Galápagos are not found anywhere else, but the introduction of tourism and invasive species like rats, cats, and flies, is threatening their homes and food supplies. For the ground finches, the introduction of blackberry bushes, which grow in dense thickets, prevents them from reaching the ground to feed.

Coming full circle, Darwin’s great-granddaughter, Dr Sarah Darwin, is now working with the Galápagos Conservation Trust to try and save the birds living on these precious and iconic islands.

As well as inheriting her love of science from her great-grandfather, she’s also a fan of the birds that he focused on instead of the finches, recently saying,

“The mockingbirds hold a particular place in my heart, they are cheeky, lovely, jaunty little birds and I particularly love them."

References and further reading

Darwin Online ‘Where do Darwin’s finches come from?’

New Scientist - ‘Evolution in action, by Darwin's finches’

Discover Magazine - ‘Are Darwin's Finches One Species or Many?’

Daily Telegraph - ‘Darwin's great-great granddaughter warns birds which inspired theory of evolution are at risk of dying out’