Back to the womb - fish, fraud and dodgy embryology

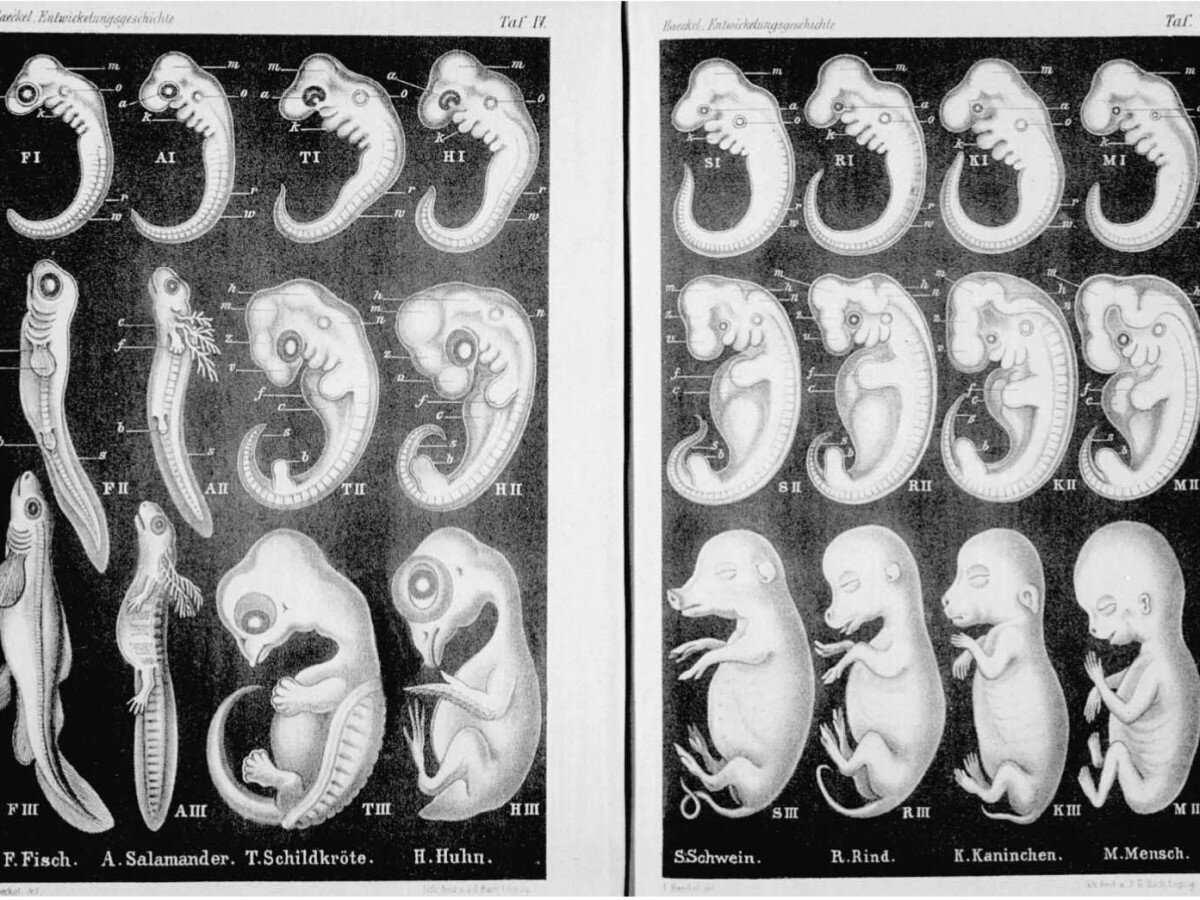

Haeckel’s embryo drawings from his 1874 book Anthropogenie, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Born in 1834, Ernst Haeckel was a German zoologist with a flair for illustration - and a knack for creating incredibly detailed and widely shared scientific images.

As we heard in episode 27 of our last series, his tree of life diagram was widely reproduced, despite not representing Darwinian principles very accurately. But that’s not his only controversial viral meme.

Haeckel played a crucial role in spreading Darwinian ideas in Germany, but he wanted to go deeper. At the time, scientists didn’t have that many fossils to provide evidence of the evolutionary process - and there was certainly nothing like the DNA-based molecular evolution techniques we have today - so Haeckel and his contemporaries wondered whether embryos could teach them about evolution instead.

In Haeckel's time, it was widely accepted that early embryos of mammals look very similar in the early stages of development. This observation didn’t escape the notice of Darwin himself, who wrote in the Origin of Species:

“The embryos, also, of distinct animals within the same class are often strikingly similar: a better proof of this cannot be given, than a circumstance mentioned by Agassiz, namely, that having forgotten to ticket the embryo of some vertebrate animal, he cannot now tell whether it be that of a mammal, bird, or reptile.”

To explain these similarities, Haeckel created a theory he called the Biogenetic Law. He even came up with a catchy motto, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”, to sum up his ideas.

Essentially, this means that an organism’s embryo goes through a series of developmental stages that recapitulates the trajectory of its evolutionary journey.

Accordingly, Haeckel believed that human embryos go through stages where they show characteristics of their more primitive ancestors, such as fish gills or monkey tails, mapping out the journey from flopping fish to swinging ape to proud, upstanding human.

This also reflects his belief in 'directed evolution,' progressing from simpler to higher forms, with humans obviously being at the top of the evolutionary tree.

Without being able to take photographs of real embryos to support his ideas, Haeckel turned to his sketchbook.

He produced a series of iconic drawings of embryos from a range of species, captured at various points through development, to support his theory. And he published them in two books - Anthropogenie (The Evolution of Man) and Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, or Natural History of Creation.

The best-known version of this picture shows a grid of embryos, with eight columns of different vertebrate species - fish, salamander, tortoise, chicken, pig, cow, rabbit and human - shown in three rows that capture them at different stages in development.

In the top row, representing the earliest stage of embryonic development, they all look like almost identical jellybeans. By the bottom row of the image, the embryos look much more like fish or birds or tortoises or whatever they will eventually become.

Haeckel used these pictures to show that vertebrate embryos all look very much the same in the early stages of development, regardless of which species they are. It was a visually striking image in a time when many people had never seen a picture of an embryo.

But, just like many of the most popular viral images that do the rounds today, the true story was a little bit more complicated.

As well as being a scientist, Haeckel was an outspoken political character with plenty of enemies. Almost immediately after their publication in the 1860s, other researchers began to challenge his illustrations and his ideas. Science fight!

His peers accused him of exaggerating the similarities between embryos, with Ludwig Rütimeyer, professor of Biology at the University of Basel even accusing him of using the same print to produce them all:

"One and the same, moreover incorrectly interpreted woodcut, is presented to the reader three times in a row and with three different captions as [the] embryo of the dog, the chick, [and] the turtle".

Rütimeyer accused Haeckel of "playing fast and loose with the public and with science."

Haeckel fought back, arguing that it was impossible to tell the difference between vertebrate embryos at this very early stage, which was true using the instrumentation available at the time. Nonetheless, he corrected his error in the next edition of his book.

Unfortunately, the damage was already done, and Haeckel has not escaped the accusations of dodgy embryology ever since.

Moreover, the idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny has failed to stand up to scientific scrutiny. As we’ll discover in part two, although early vertebrate embryos do look curiously similar at first glance, so-called ‘higher’ organisms like humans or cows don’t literally pass through a fishy phase in the womb. And closer examination of a wider range of species reveals crucial differences in the form and structure of embryos even at a very early stage.

Still, Haeckel’s embryo images were widely reproduced despite their controversy - proof that publishers do love an eye-catching image above all else. The accusations of fraud were less well known in the US, and Haeckel's illustrations found their way into many American textbooks, where some of them remain until this day.

But that’s not the end of the story.

In 1997, the journal Science published an article called ‘‘Haeckel’s Embryos: Fraud Rediscovered’, claiming that Haeckel had intentionally misrepresented embryological development.

To demonstrate the point, Haeckel’s drawings were lined up against photographs of the actual corresponding embryos taken by British embryologist Michael Richardson, who was quoted in the article as saying ‘‘It looks like it’s turning out to be one of the most famous fakes in biology’’

The story was, of course, picked up by the press and jumped on by creationists and advocates of intelligent design who used the charges of fakery as proof of widespread scientific fraud in the field of evolutionary research.

But it seems that the Science article that charged Haeckel with fraud may have contained a few of its own misleading images. Historian of science Robert Richards published a paper in 2009 arguing that Michael Richardson's images did not offer a fair comparison with Haeckel's drawings.

Haeckel distinctly stated that his pictures did not include yolk sacs or any other maternal material, while Richardson's photographs clearly include yolk sacs, making the embryos appear more different to Haeckel's images than they are in reality. Richards reengineered the photographs to show that the embryos weren’t so different after all.

However, current evidence does show that some of Haeckel’s images were indeed inaccurate. For example, his illustrations of Echidna or spiny anteater embryos show them growing little limb buds at the same early stage as other mammals, but Echidna embryos actually develop their limb buds much later on.

Despite his errors, Haeckel made many contributions to science. He discovered, wrote about and drew thousands of new species, engaging the public in science and spreading the word about evolution.

It would be a shame to discount his contributions and brand him a fraud because his work wasn’t always completely accurate.

As for Haeckel’s famous embryo pictures, some biologists argue that they still have a place in teaching developmental biology today.

Although the images may be inaccurate, the fundamental point that the illustrations are showing is correct: the more closely related two species are in evolution, the more similar their early-stage embryos will appear, even though we don’t literally become fish and monkeys as we grow in the womb.

And finally, as someone who studied developmental biology, I still find the neat little drawings to be utterly entrancing. In fact, I even used Haeckel’s embryo grid as the wallpaper on my very first computer at university.

The science may not be 100 per cent correct, but in my opinion they are still 100 per cent art.

References and further reading

Early Evolution and Development: Ernst Haeckel, Understanding Evolution

Copying Pictures, Evidencing Evolution, Public Domain Review, Nick Hopwood

Haeckel’s embryos: the images that would not go away, Cambridge University.

Embryonic Evolution Through Ernst Haeckel’s Eyes, The Scientist

Haeckel's Embryos: Fraud Rediscovered, Science, 1997, Elizabeth Pennisi