A tale of two Lederberg: Esther’s work on viruses led to a Nobel for her husband, while she struggled to get tenure.

All in History of genetics

Mighty Mouse

Mice are arguably the perfect model organism for human biology, putting on their little white furry lab coats to help researchers understand and treat a huge range of human ailments.

Pretty white for a fly guy

Forget your leggy blondes and busty brunettes, muscled hunks and sexy, skinny guys, the undisputed top model in the world of genetics is the tiny fruit fly.

Hey, buddy

First discovered by sixteenth century doctor and botanist Johannes Thal, Arabidopsis has long been a firm favourite of geneticists who prefer their subjects to stay still in a pot.

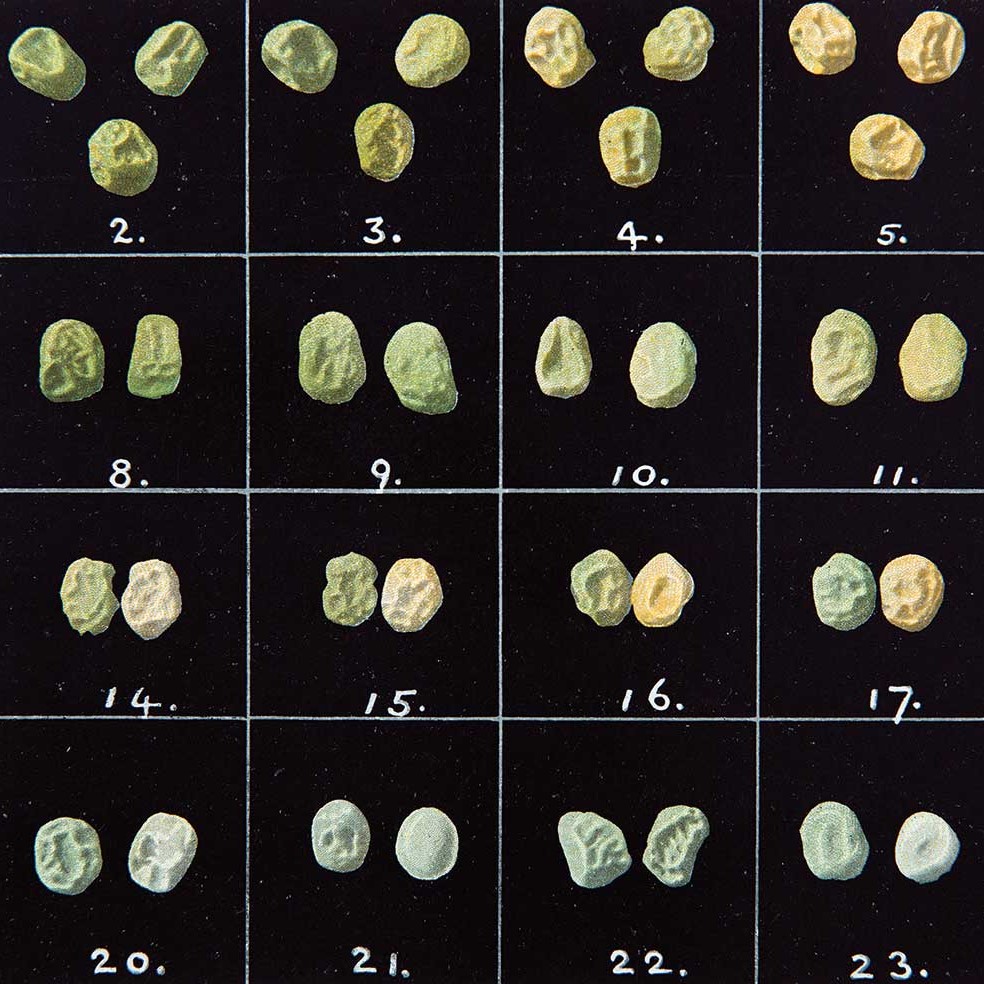

Fifty shades of peas

Gregor Mendel discovered the principles of genetics. But it turns out that people are not peas… and even peas are not peas.

Hunting for Huntington's

The year is 1872. A young American doctor, George Huntington, has just started his career, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, who were general practitioners in the prosperous Hamptons area of New York. Graduating from Columbia University the year before, at the tender age of 21, George is keen to make an impression on the medical world.

Nobel viruses

It may sound strange, but a chicken virus has won three Nobel prizes. Not bad work for a tiny bag of genes loitering on the edge of life.