A growth industry: The story of human growth hormone

Click here to listen to the full podcast episode

Growth hormone is a pretty magical biological substance produced by the pituitary gland, a pea-sized gland at the base of the brain and helps you - you guessed it - grow. As a result, people who don’t produce enough growth hormone and have severe growth hormone deficiency can be very short.

A famous example of growth hormone deficiency was Charles Sherwood Stratton, also known as General Tom Thumb, a circus performer who lived in the 1800s. Despite being a relatively large baby at over 4kg, by the age of 21, he was just 89 cm tall, shorter than the average three-year-old.

By the 1900s, doctors began to understand growth hormone deficiency and started looking for ways to treat the condition. But unfortunately, unlike insulin, extracting growth hormone from animals did not provide any benefits for people because the structure of animal growth hormone is too different from its human equivalent, and the effects of growth hormone are species-specific. So to treat growth hormone deficiency in humans, researchers needed to extract it from humans.

By the 1950s, scientists began extracting growth hormone from the pituitary glands of human corpses to treat children with severe growth hormone deficiency. Supplies were limited, but around 27,000 children were treated in this way between 1963 and 1985. But in the mid-1980s, alarm bells began to ring.

Several patients in the US who had been treated with human growth hormone derived from corpses developed Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a neurological disorder commonly known as CJD.

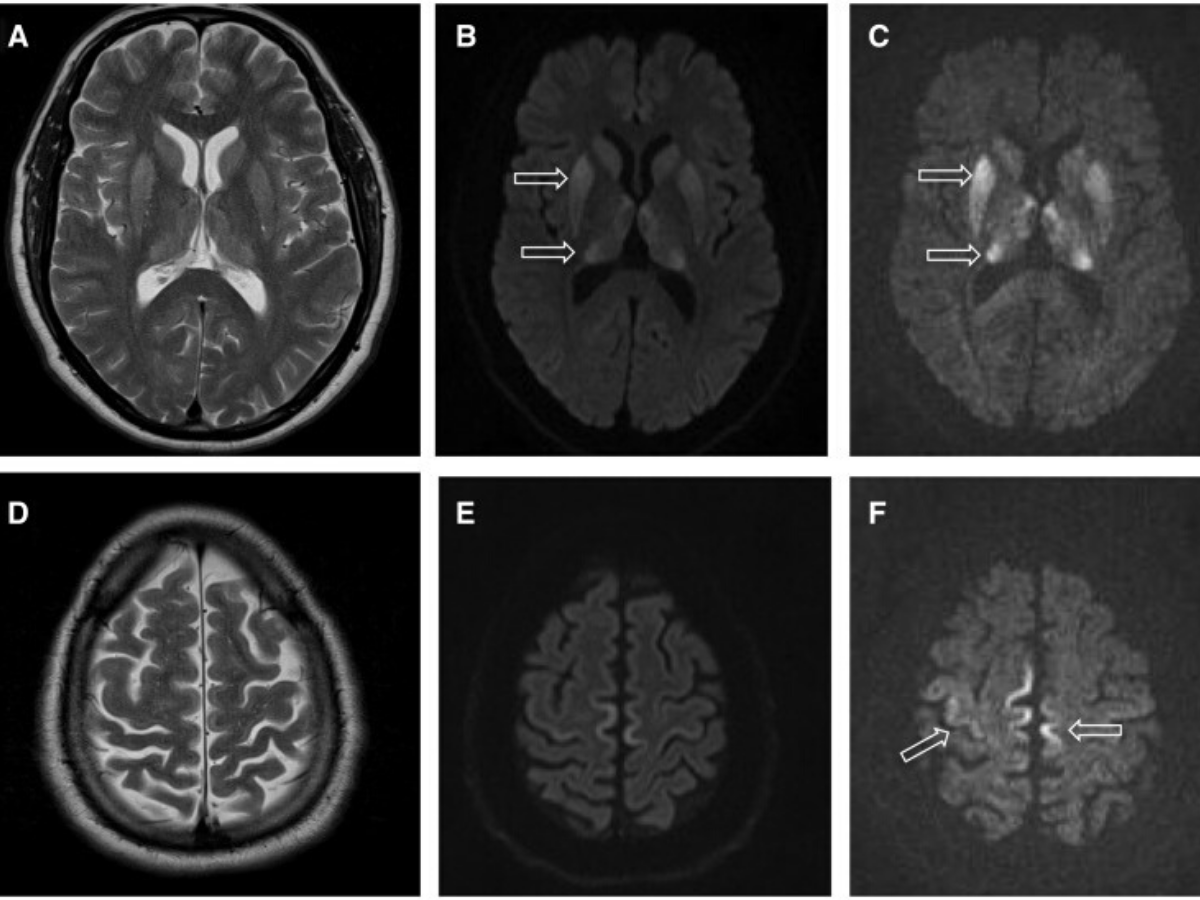

CJD is a fatal condition caused by infectious misfolded proteins called prions. Prions transmit their misfolded shape to normal proteins in the central nervous system, so the number of abnormal proteins increases rapidly. The misfolded proteins disrupt the central nervous system by affecting nerve signalling and damaging neurons, leading to brain damage and ultimately death.

CJD can be transmitted between people by contact with contaminated brain tissue or spinal fluid that transfers the infectious prions. Unfortunately, when human growth hormone was extracted from the pituitary glands of people who had CJD prions and used to treat children with growth hormone deficiency, the disease was passed on too.

As a result of the reports, the UK stopped treating people with natural human growth hormone in May 1985, but by March 2000, 34 out of the 1,900 people who were treated with the substance in the UK had died of CJD. And to add to the troubles caused by the treatment, recent research has suggested that the therapy may have also transmitted other faulty proteins that may increase the chances of people developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

In the face of this tragedy, researchers raced to develop a safe, synthetic version of human growth hormone. After their success with insulin, the scientists at Genentech were trying to create recombinant processes for producing more complicated hormones, like human growth hormone whose biochemical structure was discovered in 1972.

But while insulin has 51 amino acids in total, human growth hormone has 191. The scientists at Genentech realised that the gene would be too large for them to synthesise completely, as they did for insulin, so they synthesised part of the gene directly, letter by letter, but created the other part using cDNA, which is DNA created using the messenger RNA encoding for the protein as a template.

The Genentech team succeeded in creating the first recombinant human growth hormone in 1981, which was approved rapidly by the FDA in the wake of the CJD scandal and introduced as a therapy for severe growth hormone deficiency in 1985.

While the use of human growth hormone was severely limited before the introduction of the recombinant version in 1985, its development and unlimited availability led to its use in several additional conditions, including in children with chronic kidney disease, Turner syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome. But it doesn’t stop there.

Since the introduction of recombinant human growth hormone, this list of indications has grown substantially. It now includes conditions like ‘idiopathic short stature’- which means a person has no underlying health issues but is less than two standard deviations below the average height for their age. In the UK, that is equivalent to an adult height of less than 5’3 for men and 4’10 for women. The definition seems sketchy given that thanks to the distribution of heights in the population, around 2% of people will always be right down the lower end of this scale.

In recent years there has been some controversy about the widespread use of human growth hormone and whether simply being short, with no underlying medical conditions, is a disease that needs curing with expensive treatment like human growth hormone, especially as it’s children being treated. Recent analyses have also suggested that increases in height from human growth hormone are modest, with scientists suggesting the benefits are not worth the frequent injections or the price tag of approximately $52,000 per inch of extra height.

Although human growth hormone is responsible for growth in children, it also helps maintain tissues and organs in adults. However, as we reach middle age, the amount of human growth hormone we produce begins to drop. This drop has led some people to wonder whether maintaining high levels of human growth hormone in adulthood might help reduce some of the effects of ageing, like decreased bone and muscle mass. As a result of these theories, recombinant human growth hormone has been a popular but illegal performance-enhancing drug since the 1980s.

Studies have shown that human growth hormone can increase lean mass and reduce body fat, but it also comes with side effects, including an increased risk of diabetes, joint pain, muscle pain, fluid retention and high blood pressure. What’s more, clinical trials have failed to show that human growth hormone increases athletic performance.

Even so, the successes of somatostatin, insulin and human growth hormone jump-started the biotechnology industry, and the list of recombinant protein therapies has continued to grow in the decades since.

Treatments approved by the FDA now include Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), a female sex hormone that was once isolated from urine, clotting factors that were once harvested from blood, and several more.

We’ve come a long way from the early days of genetic engineering and synthetic hormones in the 1980s, and even further from Banting and Best’s early experiments a century ago. The era of biological drugs is well and truly here to stay.

References:

Children’s growth hormone made from the glands of infected corpses - Independent

Childhood hormone treatments may have spread alzheimer’s proteins - New Scientist

Growth hormone - Society for Endocrinology, You and your hormones

Idiopathic Short Stature: Conundrums of Definition and Treatment - Int J Pediatr Endocrinol.

Growth hormone and aging: A challenging controversy - Clin Interv Aging

An overview of FDA-approved biologics medicines - Drug Discovery Today