Giant steps - Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant

Click here to listen to the full podcast episode

The Irish giant’s dying wish was to be buried in a lead coffin. At sea. Off Margate.

Born in Londonderry, Northern Ireland in 1761, Charles Byrne is said to have grown “like a corn stalk”, quickly reaching a staggering 7 foot 7 inches. In 1782, at the age of 21, he travelled to London, where he sought – and to some extent found – his fame and a small fortune.

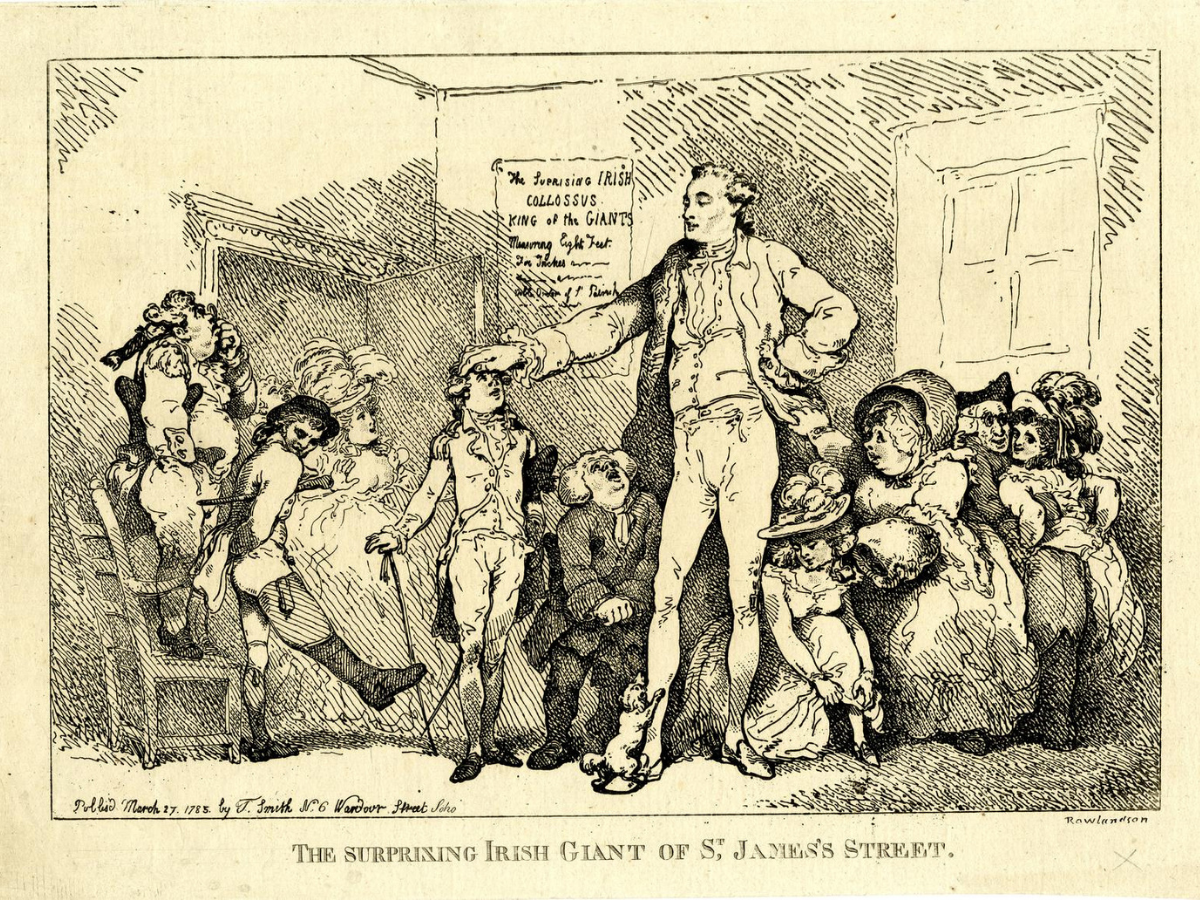

Billed as a “modern Colossus” and described by one newspaper as “the most extraordinary curiosity ever known, or ever heard of in history,” Byrne caused an overnight sensation,. He entertained packed halls of fee-paying Georgian guests, got to meet King George III himself and even inspired a hit pantomime at the Theatre Royal on Haymarket - Harlequin Teague or the Giant Causeway. The celebrity of the Irish giant might have reached even greater heights, but hit with tuberculosis, he began drinking heavily and within a year he was dead.

A newspaper at the time noted that “a whole tribe of surgeons put in a claim for the poor departed Irishman surrounding his house just as harpooners would an enormous whale.” But having been told Byrne’s dying wish, his friends arranged for the burial at sea. What they didn’t know is that somewhere between the undertakers and the very long lead coffin sinking beneath the waves of the North Sea, Byrne’s body vanished.

But he wasn’t gone forever. A few years later, the skeleton of the Irish giant appeared as an exhibit in the private museum of the anatomist, surgeon and collector of biological oddities John Hunter. One story has it that Hunter paid the undertaker £500 to switch out the body and fill the casket with stones to avoid suspicions being raised en route to Margate. In an alternative telling, Hunter is said to have simply paid off Byrne’s bribable friends.

Either way, it seems likely that the famed surgeon boiled up the body, stripped it to the bones and secreted them until London’s chattering classes had started chattering about something else. After Hunter’s death, the British government purchased his large and varied specimen collection – including the Irish giant – to establish the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in central London. Byrne’s skeleton was still on display, alongside jars of pickled body parts, bones and all sorts of other bits and bobs, until the museum closed for refurbishment in 2017.

While Byrne may not have got his wish to rest in peace at the bottom of the sea, one upside of this giant body-snatching saga is that scientists have repeatedly studied his skeleton in their efforts to understand why Byrne – and others like him – sometimes grow and grow and grow.

The most common cause of becoming unusually tall is having an adenoma – a type of benign tumour – on the pituitary gland, a pea-sized organ at the base of the brain responsible for the production and secretion of several vital hormones. One of these is growth hormone, a protein messenger that instructs bones and associated tissues to grow, partly by boosting production of the hormone insulin-like growth factor 1.

If growth hormone is produced in excessive amounts during childhood, it can result in what’s known as pituitary gigantism. Once puberty is over, the levels of growth hormone normally tail off, the bones fuse and cannot get any longer. But if growth hormone continues to be released into adulthood, which can happen with a pituitary adenoma, this causes bones to become thicker and thicker, a condition known as acromegaly.

In 1909, the so-called “Godfather of neurosurgery” Harvey Cushing, famous for the discovery and description of Cushing’s Disease, another hormone disorder, had a hunch that Charles Byrne’s towering stature had been the result of a childhood pituitary adenoma and he persuaded the conservator of the Hunterian Museum Arthur Keith to let him take a look at Byrne’s skull.

As predicted, the pituitary fossa, the cavity that houses the pituitary gland, was about twice the normal size, a result of an adenoma that Keith described “had grown upwards and forwards, causing a very distinct impression on the floor of the cranial cavity.”

The thickening of Byrne’s skull suggests that his anterior pituitary must have continued to secrete growth hormone beyond puberty and that he’d suffered from acromegaly too. John Hunter could easily have described this pituitary enlargement more than a century earlier if only he’d taken the time to look but, as Cushing wryly noted, “his passion as a collector exceeded his thirst for knowledge.”

The scientific interest in Charles Bryne didn’t stop there. Although Byrne was the only giant from the Irish village of Littlebridge, the Knipe brothers – identical twins from a nearby village– were also pretty tall at over 7 feet apiece. With the suggestion that these three giants were related, it seemed reasonable to imagine there might be some genetic basis to pituitary gigantism.

Around 15 years ago, researchers studying the genetic makeup of a Finnish family with a history of pituitary adenoma drew attention to the gene encoding the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein or AIP for short. Subsequent investigation has confirmed it plays a predisposing role to growing into a modern-day giant, with nearly one in three of those with pituitary gigantism having an alteration in the AIP gene.

Marta Korbonits, an endocrinologist at Queen Mary University of London with a special interest in pituitary adenomas, began to look for AIP mutations or deletions in her unusually tall patients and found a lot, including four families from Northern Ireland. Is it possible, she wondered, that Charles Byrne could also have had issues with his AIP?

With permission from the Hunterian Museum, Korbonits removed two teeth from the skull of the Irish giant, succeeded in extracting DNA and discovered a single DNA ‘letter’ change in the middle of Byrne’s AIP gene. When she sequenced the DNA from patients with pituitary adenomas currently living in Ireland, she found they were all carrying the exact same alteration.

Korbonits has calculated that the variation probably first appeared in a single common ancestor who had lived – probably in Ireland – between 57 to 66 generations earlier. Follow-up research suggests that one in 150 people in the region where Byrne grew up carry this gene variant, far higher than the 1 in 1000 in Belfast, which is why this part of Ulster has been referred to as “a giant hotspot”.

The identification of alterations in AIP and other genes that increase the risk of developing a pituitary adenoma is becoming a key tool in speeding up diagnosis of gigantism and acromegaly. This is important because apart from excessive growth, pituitary adenomas are associated with a range of health conditions including delayed puberty, loss of vision, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, sleep apnea, arthritis and thyroid cancer to name just a few.

The longer the delay in diagnosis, the more of these health problems accumulate, with an inevitable reduction in lifespan. With early diagnosis, more treatment options become available, including surgery, radiation or chemotherapy to reduce the size of the tumour or medication to counteract the actions of excessive growth hormone and its mental, physical and hormonal toll.

“Diagnosis is key to fighting the debilitating effects of this condition,” write the authors of a recent review looking at the importance of early diagnosis. “Delays in diagnosis only prolong suffering and the battle of the patient being in control of this disease instead of the disease being in control of the patient.”

From the vantage point of the 21st century, John Hunter’s acquisition of Charles Byrne’s body more than two centuries ago looks decidedly dodgy and there have been calls for the giant’s remains to be returned to Ireland. The Hunterian Museum – due to reopen in 2023 – is updating its displays and has yet to announce the fate of the skeleton.

Whatever happens, it is fair to say that Byrne – once touted as “the tallest man in the world” – has made a giant contribution to science.