The darkest side of genetics

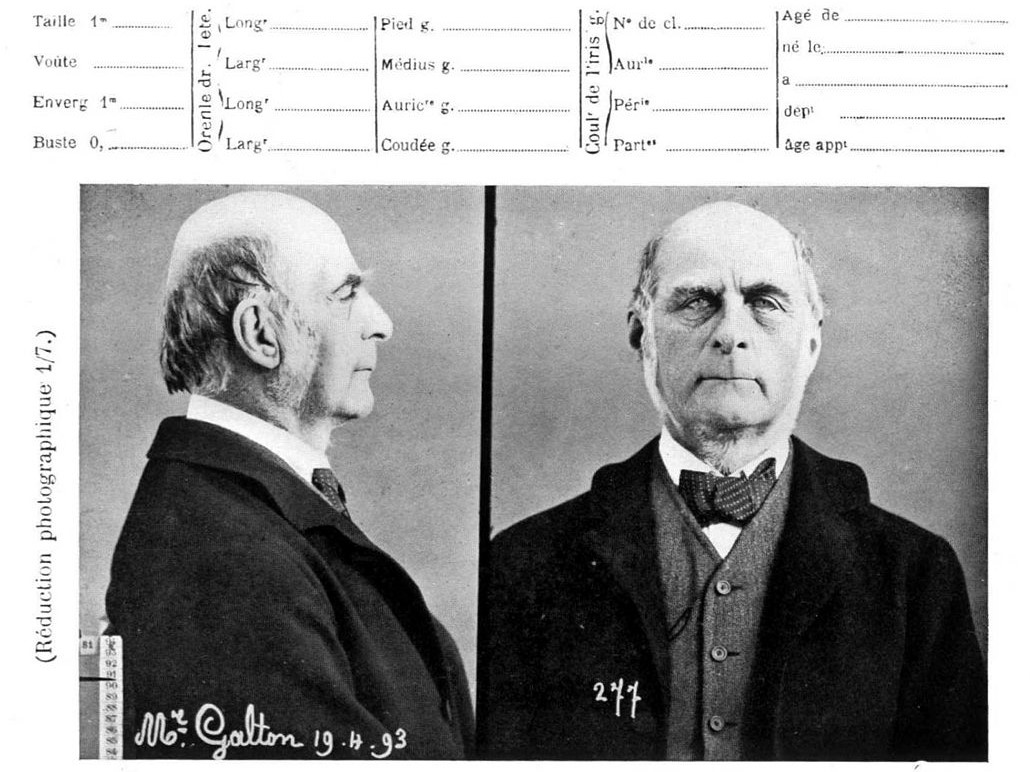

Photograph and Bertillon record of Francis Galton (age 73) created upon Galton's visit to Bertillon's laboratory in 1893. Via Wikimedia Commons

You’ve probably noticed that geneticists do love to bang on about Charles Darwin - arguably one of the greatest scientific minds of all time, and the man who’s remembered for coming up with the theory of evolution by natural selection (or, at least, being the first to so completely and coherently publish his ideas about it).

One person who had huge admiration for Darwin was his cousin, Francis Galton, who was also a scientist with a keen interest in similar themes of heredity and evolution.

Galton is widely regarded as having a brilliantly inventive mind, coming up with innovations such as forensic fingerprinting, weather maps and (my personal favourite) the Gumption Reviver - a portable dripping tap designed to sit over a student’s head in lectures and keep him awake.

But what really sealed his legacy was his establishment of the field of anthropometrics - that’s what we’d probably now call biometrics - which basically means Count All The Things.

Galton was obsessed with measuring people. Not just the easy stuff like height, weight, eye or hair colour, but everything. Strength, breathing capacity, reaction time, hearing and vision, colour perception, judgement of length and intelligence.

He was also the originator of the idea of the baby book, measuring and tracking infants from birth to see where they fall in relation to average milestones and markers. It’s something that will be familiar to any parents today who have proudly boasted (or secretly worried) that their baby falls in a particular percentile for a certain measurement.

It was this obsession for measurement that led Galton to the infamous idea for which he’s best known and the word that he coined to describe it: eugenics.

As a student at Cambridge University, Galton had spotted that the top students also had relatives who had done well there, as was convinced that this success must be down to heredity, rather than upbringing. Insert massive eye roll and discussion of privilege here…

This belief of the power of nature over nurture was reinforced through his travels in Africa as a young man, where he mused on the what he referred to as “the mental peculiarities of different races”, but what we’d now probably describe as massively racist stereotypes.

He even put together a book “Hereditary Genius,” published in 1869, in which he write long lists of “eminent” men—judges, poets, scientists, even oarsmen and wrestlers—to show that excellence ran in families. And obviously, only in men.

Galton started to apply statistics to analyse all his data, dividing populations into groups according to traits. And it’s here that things start to really go awry.

Focusing on what were considered to be undesirable characteristics, such as weakness, savagery or ‘feeble-mindedness’, Galton wondered whether it might be best to simply… get rid of the people who fell into those groups, either by persuading or forcing them not to have babies.

It was an idea that fell on fertile ground in the uncertain political climate of the early 20th century, both here in Europe and in North America. At the same time as the world was opening up through international travel and commerce, states were enacting eugenic policies targeting certain groups for enforced sterilisation and holding ‘beautiful baby’ competitions. No prizes for guessing what a ‘beautiful baby’ looked like…

But the example that stands out the most and leaves the darkest stain on the history of 20th century Europe is the massive programme of eugenic horror carried out by Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler.

Rather than just deciding that certain people shouldn’t breed, the Nazis set out to systematically eradicate whole populations.

During the Holocaust, some 6 million Jews were murdered, along with millions more deemed ‘undesirable’ by the Nazi’s eugenic standards including Slavs, Poles, the Roma, the "incurably sick", disabled and gay people.

The Nazis aren’t the only example of using eugenic ideas and bad race science to inflict genocide. Another case is in Rwanda, where Belgian colonisers used eugenic ‘science’ to create artificial racial categories, where previously the divisions between Hutu and Tutsi had been social.

They drew on Galton’s biometric techniques such as skull measurement to divide and conquer the population through the early 20th century, ultimately leading to the genocide of up to a million Tutsi people in the mid-1990s.

Even something that we think of as good from a global public health and women’s rights perspective - increasing the availability of contraception - has a whiff of eugenics.

Although there is debate about their motivations, language and legacy, early 20th century birth control pioneers like Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger - the founder of Planned Parenthood - certainly did embrace at least some of the ideas and words of the eugenics movement about who should or shouldn’t be having babies, rather than enabling women to control their own personal choices and fertility.

On a wider level, countries like Britain and the US used financial leverage to encourage poorer countries to control their rapidly-growing populations, culminating in an outrageous programme of enforced sterilisation of men in India in the mid-1970s under Indira Ghandi’s rule. And there are still forced sterilisations going on in India and other parts of the world today.

My sister Helen and I explored the legacy of Galton’s eugenic ideas in our BBC Radio 4 series, Did the Victorians Ruin The World?

We came to the conclusion that while it’s arguable that pretty much everyone in polite, white Victorian society was probably a wee bit racist, even by standards of the time Francis Galton was right out there.

A lot of his ideas are based on fairly grim racist or sexist assumptions - for example, he would use a secret glove-based device in his pocket to rank passing women as ‘attractive’, ‘indifferent’ or ‘repellent’, eventually enabling him to rank the relative hotness of women in different British towns (London having the most hotties, Aberdeen the least, apparently) like some kind of gross Victorian lad’s mag.

He was also somewhat into measuring the size of African women’s buttocks and breasts, and apparently even his invention of fingerprinting was because he couldn’t tell the difference between people who weren’t white and wanted to characterise and sort them better. And, of course, there’s the whole eugenics thing.

This dubious legacy has led to some difficult conversations for organisations like University College London (UCL), which hosted the The Francis Galton Laboratory of National Eugenics and professorship or Chair of Eugenics, endowed by £45,000 from Galton’s own will.

The lab was renamed The Galton Laboratory of the Department of Human Genetics & Biometry in 1963, but there’s an ongoing and heated debate about whether the university should keep honouring the name of a deeply problematic man who described Africans as “lazy, palavering savages” or just get rid of it already.

It’s a problem that also faces the Galton Institute. They’re a charity independent of UCL, which was originally founded in 1907 as the Eugenics Education Institute but is today dedicated to addressing the issues raised by the study of human heredity and completely rejects eugenic theory and practices.

But while it is tempting to erase Galton and all his awful ideas forever, the current president, Professor Veronica Van Heyningen, suggests that acknowledging the history and properly addressing the social, scientific and political context of eugenics is a powerful way to understand how these abuses of genetic science arise and stop them from happening again.

“I fully acknowledge that Galton was a terrible racist,” she says in an interview with the Observer newspaper. “But he also played an extremely important role in developing the science of genetics, and it is reasonable to honour him by giving his name to institutions like the one I now run. However, this whole debate raises a real problem: how can we redress historical wrongs?”

Unfortunately, all this historical reflection isn’t preventing racist, eugenic arguments springing up in the darker corners of the internet and increasingly out in the open, fuelled by the misunderstanding and mis-use of modern genetic data.

By mapping the breadth of human genomes across the world, we can start to understand the true patterns of human genetic diversity and how it might influence health outcomes, such as understanding how specific genetic variants affect whether you should take a particular drug.

Ultimately, this kind of research tells us that yes, there’s a lot of complex diversity out there in the world, but also that the simplistic pseudoscientific classifications of racial differences - exemplified by people like Galton - break down in the face of modern genetic analysis.

As geneticist and science writer Adam Rutherford so neatly puts it, humans are “horny and mobile”, and have been over the many tens of thousands of years of our evolution and migration across the planet.

We all share the same genome - the 6-billion letter recipe book that makes a human being - with 99.9% similarity between any two random people. And we all deserve the same dignity and respect.

The one irony in all of this is that despite his own self-professed genius, Galton himself died childless. Yet the unwelcome return of racist, eugenic ideology, shows that his ideas continue to spawn dark thoughts and actions. History repeats itself - we should be very careful to listen.

References and further reading

What Margaret Sanger Really Said About Eugenics and Race - Time

'Extreme Measures': Eminent Victorian, Alas. Dick Teres, New York Times

Auschwitz to Rwanda: the link between science, colonialism and genocide - The Conversation

IN 1976, MORE THAN 6 MILLION MEN IN INDIA WERE COERCED INTO STERILIZATION - Mel Magazine

Why racism is not backed by science. Adam Rutherford, The Guardian

Measure for Measure - The strange science of Francis Galton. Jim Holt, The New Yorker

Top university split in row over erasing ‘racist’ science pioneers from the campus. The Observer

Hubei woman dies after forced sterilisation. South China Morning Post